Number of repetitions

Choosing to remember with Anki

- Planted:

- Last watered:

I began using Anki in July of last year to aid my memory and learning. Although it’s still a relatively new habit for me, I’m already confident that it’ll be a key learning tool for the rest of my life with compounding benefits over time.

Anki is free flashcard software that automates the timing of card review. So for example, let’s say you write a new flashcard that asks, "About how many neurons do humans have?" (about 100 billion). Anki presents that card for review immediately. You remember it and mark it as correct. The next day it presents the same card, which you remember again and mark as correct, so Anki waits a full week to present it a third time. If you get it right again, Anki will wait a month or so to surface it, and so on. If you get it wrong, the clock resets.

There are more layers to the software, but that’s the basic premise. I’ll cover both the why of Anki for me and observations from my first six months using it.

Spaced repetition and forgetting curves

Anki’s automated review timing is an implementation of spaced repetition. Physical flashcards are an even simpler form. The idea is that you should allow some time to forget what you’ve learned, then test yourself just before forgetting. Each act of recall strengthens the memory trace in your brain for that knowledge and also makes neural connections to new things you’ve learned since the last retrieval.

Spaced repetition is visualized by a forgetting curve, which plots retention over time. Cognitive psychologists have been plotting forgetting curves since Hermann Ebbinghaus’s self-observation study of memory in 1885. The forgetting curve below is interactive—try sliding the number of repetitions and observe how retention changes over time.

When we learn something, retention starts at 100% then drops gradually toward 0%. With each retrieval, retention jumps back to 100% and begins to decline again, but at a slower rate. Note that the curve flattens with each retrieval as the memory trace becomes more durable. Also note that the forgetting interval increases between each retrieval because memory traces become more durable with each marginal act of recall.

The plot is not a perfect science reflecting the precise rate of forgetting or the optimal retrieval interval, but it should be directionally correct.

I also created an interactive forgetting curve on Observable to calculate and plot retention with varying repetitions. The math I came up with is arbitrary, but feel free to take a look and suggest any improvements! I wrote about the calculations in that Observable notebook.

Memory’s role in thinking

I first learned about Anki from my partner when she was in medical school (med students use Anki heavily, often reviewing hundreds of cards per day). I thought it was neat, but I didn’t see the appeal beyond high-volume memorization domains like medicine and law. Then my coworker Danny mentioned that he’d started using Anki a few years prior after reading Augmenting Long-Term Memory by Michael Nielsen. From the essay:

Anki can be used to remember almost anything. That is, Anki makes memory a choice, rather than a haphazard event, to be left to chance. I’ll discuss how to use Anki to understand research papers, books, and much else. And I’ll describe numerous patterns and anti-patterns for Anki use. While Anki is an extremely simple program, it’s possible to develop virtuoso skill using Anki, a skill aimed at understanding complex material in depth, not just memorizing simple facts.

I read that essay, and it immediately clicked for me. I recommend reading the full essay if you’re interested—I found it highly energizing. Two key points stand out: that you can choose to remember (and choose what to remember), and that foundational knowledge is critical for accruing expertise, solving problems, and boosting creativity.

Building on Nielsen’s claim that Anki can be used for much more than memorizing simple facts, the book Make It Stick—which covers effective learning techniques supported by research—makes the case that memory is crucial for thinking and developing expertise. From the book:

Memory plays a central role in our ability to carry out complex cognitive tasks, such as applying knowledge to problems never before encountered and drawing inferences from facts already known.

...

All new learning requires a foundation of prior knowledge.

...

Mastery in any field, from cooking to chess to brain surgery, is a gradual accretion of knowledge, conceptual understanding, judgement, and skill. These are the fruits of variety in the practice of new skills, and of striving, reflection, and mental rehersal... Mastery requires both the possession of ready knowledge and the conceptual understanding of how to use it.

Unknown unknowns

Donald Rumsfeld famously said that there are known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns. If a task requires a known known piece of knowledge or skill, we can do it. If it requires a known unknown, we can learn the prerequisite knowledge/skill then do it. But if a task requires an unknown unknown, we may not even be able to start.

Having knowledge and skills readily accessible unlocks solutions that we might not have otherwise known to reach for. For example, I like learning about and tinkering with browser APIs that I haven’t yet used in my day job or a side project, like the Battery Status API or Network Information API.

When I encounter a browser APIs I haven't heard of before, it moves from an unknown unknown to a known unknown. After learning about it or using the API, it becomes a known known. At this point, there's a fork in the road between traditional note-taking/learning and Anki. After I use the API and/or jot down some notes, forgetting sets in until the information naturally resurfaces—maybe I'm working on a feature that the API is perfect for or I read about it in a blog. In any case, that knowledge risks slipping back into known unknown territory if I don't retrieve it ("use it or lose it"). Ankifying the API eliminates that uncertainty—I can make the choice to remember it.

Danny pointed out that Rumsfeld's (un)knowns are not binary, but more like a spectrum. Our knowledge of something lies somewhere between known/unknown states.

My first 7 months of Anki

So I’ve been at it for a little over half a year:

- First card added July 29, 2023 (217 days ago)

- 486 cards added total

- 153/217 (71%) days studied

Daily studying

My initial aim was to review once per week because I thought daily would be unrealistic. Surprisingly though, my habit naturally turned into an (almost) daily morning routine without much willpower. It’s a pleasant thing to do in the morning, and there’s definitely a reward/gamification effect. Long intervals between reviews also feels burdensome because you end up with a lot of cards to review. Plus, chunking review into smaller, spaced out sessions leads to more effective learning.

Single deck

I took Michael Nielsen’s suggestion of one universal deck. Having one deck feels like a more natural representation of the brain, plus the approach of interleaving the study of different topics is known to be an effective learning technique (which I learned in Make It Stick). Categorizing would also add maintenance burden.

Notes as questions

Anki has significantly changed my note-taking style. Instead of writing notes while I learn in the form of statements, I create Anki cards in the form of questions. I still write some traditional notes, but I default to Ankifying new knowledge where it makes sense. Note: I am borrowing the use of "Ankify" as a verb from Nielsen.

When I first started, I would write questions for myself without answers as a sort of staging ground, then return to Ankify those questions the next day. I’d try writing answers from memory, sanity check my answers with a quick ChatGPT query (or Wikipedia/Google), then finally create the card.

That was good in that it optimized for refined questions and filtered out things I didn’t think were worth remembering by the next day. But it was bad because I ended up with lots of stranded questions that I didn’t get around to adding. So I reversed course and started Ankifying things I learn immediately and directly. I like this better because my rate of card creation is faster, and I can still always edit or delete the card.

Adding cards

I also found Michael Nielsen’s suggestion of Ankifying things I’m actively applying to be helpful. For example, I learned more about SVGs in Chris Coyier’s Practical SVG book on the same day that I implemented my animated Edison bulb SVG in the top right corner of this website, so I Ankified some SVG foundations in the process. I’ll sometimes also write a TIL for things I Ankify that were particularly fun to learn and worth sharing.

Deleting cards

I delete cards somewhat often because present me is often a poor judge of what future me will want to remember. Plus, I am building a better intuition for what makes a good card over time.

For example, I’ve deleted some cards I wrote for APIs early on, like “In Next.js, how do you set static or dynamic metadata for a page?” (by exporting a static metadata object or a dynamic generateMetadata() function). Although those APIs are useful, I don’t need to memorize them because (1) they are readily accessible on API docs, and (2) more importantly, I won’t forget that I want to set metadata like title and description for a webpage—I’ll know I want to do that then look up the method as needed or let Copilot fill it in for me.

Visuals

Diagrams and images can be very useful, depending on the card. I also learned from Make It Stick that there is no empirical support for the claim that preferred learning style (e.g. "visual learner") has any bearing on learning outcomes. Although learning style should fit the subject matter, e.g. visuals are important when learning geometry.

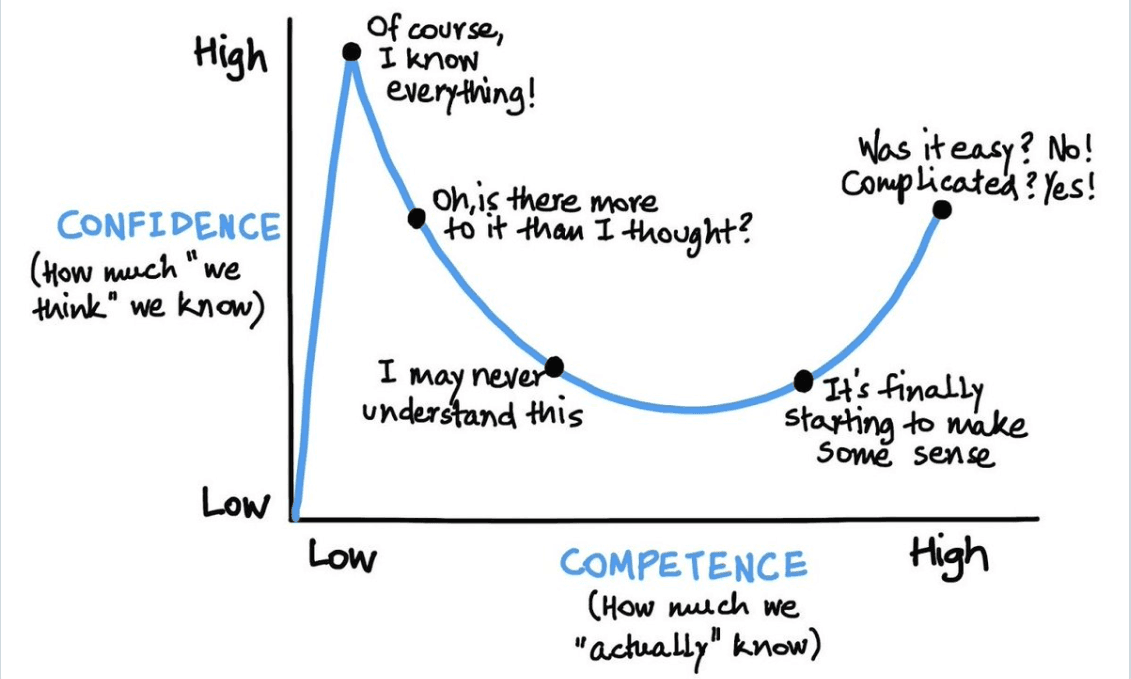

I make an effort to add visuals wherever it makes sense for a given card. For my card that asks, "What is the Dunning-Kruger effect?", I added a diagram I found on Google that illustrates the relationship between competence and confidence:

For people, I add a picture—ideally of them doing the thing I want to remember them for—to the card. My card that asks "Who is Grace Hopper?" includes the portrait of her below. While the picture doesn’t remind me that she was a pioneer of high-level programming languages, wrote one of the first compilers, or coined the term "bug" when she found a literal moth in a computer, it does remind me that she was a Navy rear admiral, which is a memory hook for the time period she worked in (because the military was at the forefront of computing innovation in the 1940s/50s).

Topics my cards cover

I Ankify things I learn from coding, books, podcasts, conversations, etc. My primary interest right now is remembering software engineering concepts, syntax, and commands, e.g. SQL commands, language model concepts, browser APIs, and so on. I also Ankify tangential topics like the history of computing and completely unrelated ones like brain anatomy and cooking science/ingredients. In short, if there’s anything I think is worth remembering for the rest of my life, I Ankify it.

Looking forward

A few years ago I used to say, "I’ll only have a high probability of remembering something if I tell someone about it or write it down." The word learning researchers use for that is elaboration (learned in Make It Stick), which is known to strengthen learning. The problem with my old strategy is that it was random. What if I didn’t have the chance to write something down or tell someone? Or even if I did, without introducing recall and spaced repetition, the learning would fade anyway.

Anki has been very empowering because it eliminates that randomness. It also increases my awareness of how what I think is worth learning changes over time. Did I add a bunch of cards a few months ago about some isolated topic that doesn’t connect to the rest of my knowledge? Maybe that wasn’t time well spent. Or maybe it was! There are obviously infinite things to learn, so I like that I am more aware of how I allocate my learning budget (i.e. time).

This is still a new habit for me, so I’m curious how it evolves. On that note, please reach out if you have your own Anki observations to share (or any observations, really)—I like talking about this stuff.